P. L. Doss

While completing a Master of Science degree in Criminal Justice at Georgia State University, P.L. Doss served a graduate internship at the Fulton County Medical Examiner’s office.

Assigned to the investigative division, she discovered how important the duties of the investigators were in helping the forensic pathologists determine the cause and manner of death. She was also able to observe the autopsies—an experience that proved to be invaluable in toughening her up for her career in law enforcement, first as a volunteer analyst in the Missing Children’s Information Center at the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, and then as a probation officer and supervisor of officers at the Georgia Department of Corrections.

She currently lives outside Atlanta, with her husband and cat.

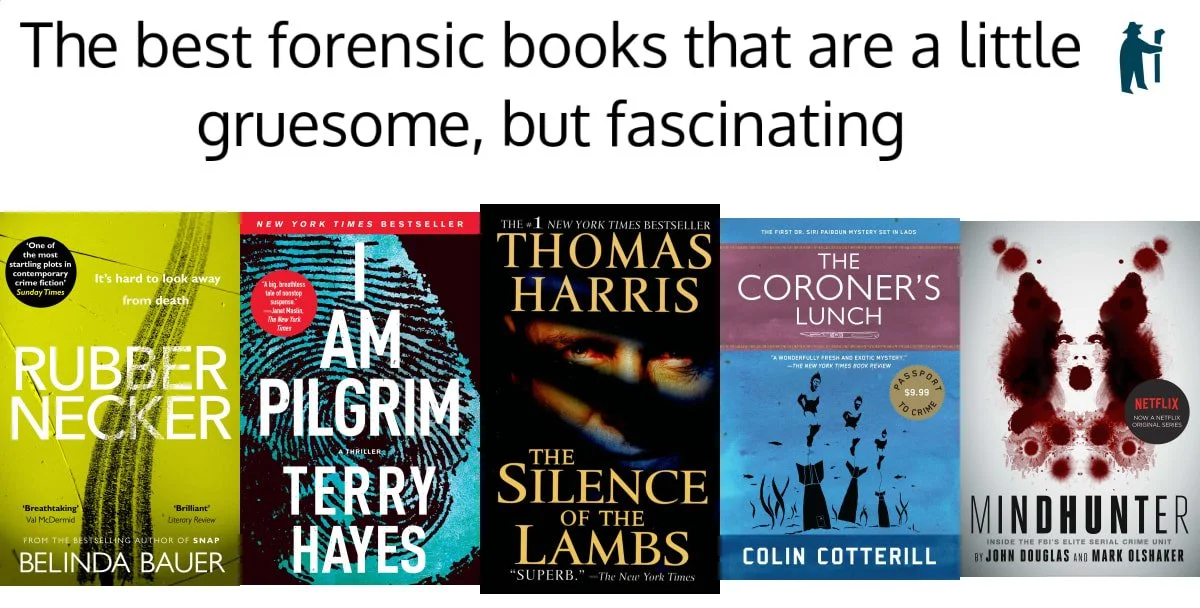

I was lucky enough to be asked to create a book list for Shepherd.com, a nifty site that curates lists by authors about their favorite books in their genres or subject areas. Click the image below to see my list, The Best Forensic Books That Are a Little Gruesome but Fascinating, or check out Shepherd’s bookshelf, The Best Forensic Science Books, to see what other authors recommend!

Working in the Atlanta criminal justice system

10 things about P.L. Doss that might surprise you

I was raised in a fairly affluent, suburban environment in Atlanta. Before Lenox Square was built, we only went downtown for dinner or to shop at Rich’s Department store once a week. As an adult, after several years of doing freelance writing I decided to get a Master’s degree in Criminal Justice (the reason behind that would take another page!). I opted to attend classes almost exclusively with people already in law enforcement: DEA agents, narcotics officers, homicide detectives, and various other investigators. I had opportunities to learn from them on a more experiential level, like the time I was invited to attend a regional seminar on serial murderers which showcased the task force that arrested Henry Lee Lucas and Otis Toole, the suspects believed to have murdered (among others) Adam Walsh.

Georgia State University allowed us to write a senior paper (a type of thesis) or do an internship at a criminal justice facility. To gain experience, I did both. My senior paper dealt with the latest information on serial murders; I was then invited to do an internship at the Criminal Justice Coordinating Council, which examined the impact of legislation on the CJ system and published a journal annually. I did another internship at the Fulton Co. ME’s Office. Although I was assigned to the Investigative Division there, because of my writing background, two of the pathologists asked me to co-write forensic articles with them, which, along with the autopsies I witnessed, got me even closer to what you might call the “darkest corners in Atlanta.”

My experience at the Missing Children’s Information Center was very sad at times, but what I discovered was that the public perception of this crime was manipulated by both the media and various CJ agencies. Most “missing” children have been taken by their non-custodial parents because of custody battles or some type of retaliation. Stranger abductions were relatively rare. We analysts traced the children through computers which had access to credit card transactions, phone bills, etc.

When I was hired by the Department of Corrections, the corners got darker. Even in my previous, relatively “safe” world, I was never under the illusion that everyone lived in an Ozzie-and-Harriet world; substance abuse, violence, mental illness, and greed cut across all socioeconomic lines. What I did get to observe was how individual pathology impacts the community, and how the community reacts to it. As a court probation officer, I saw affluent white offenders with private attorneys treated very differently (as a rule) from poor black offenders. I also saw how repeat, multiple offenders were given many “free passes” (i.e. all sentences ran concurrently) in order to alleviate jail overcrowding.

When I became a field officer in Midtown Atlanta, I was thrust into a world that seemed like another country to me. I had to make field visits to convicted felons in various housing projects, homeless shelters, and treatment centers. I also had to arrest those who’d violated their probation and transport them to the Fulton County Jail. Because the more affluent white offenders generally lived in North Fulton and were allowed to report to a probation office there, the world I inhabited was primarily African-American, and I could no longer avoid seeing the racism that is very definitely a part of the CJ system in Atlanta—and probably everywhere. I cried after visiting homes where there was no food in the refrigerator but the children were gathered around a huge TV in the living room, and despaired over pregnant probationers who tested positive for cocaine.

I’ve never lost my belief that many people can change if they’re given the opportunity AND have the desire to change, but a lot of odds are against them. When I began to supervise officers, I tried to make them understand that if they helped even a few offenders change their lives or protected the community from dangerous offenders who were in violation of their probation, they were doing some good—even if the number of people they helped seemed small or if the judges let the violent ones out again soon. (That had been a tough lesson for me to learn when I locked up a rapist for violations. The judge released him, and he then murdered four men in an Atlanta hotel a few months later.)

We may not be able to "fix" the system, and we certainly can't fix people, but we can make a difference, one person at a time.

I didn’t learn to walk until I was about two years old because I had casts on my legs, then braces, due to clubbed feet. After that, I never sat down, according to my mother.

When I went into labor with my first child (Nicole), I had complete faith in the Lamaze method of natural childbirth and took a Parcheesi game and cards to the hospital, thinking my husband and I would spend time between contractions amusing ourselves. Never happened, and I was begging for drugs before long.

I once rode in an elevator with Salvador Dali at the St. Regis Hotel in New York (he lived there at the time, and I was a hotel guest). I totally embarrassed myself by asking him if he were painting something. He gaped at me, then fled when the doors opened.

When my first forensic article was published, my mother was thrilled, until she found out the title was Investigation of a Death Caused by Rectal Insertion of Cocaine. It wasn’t really something she could put on her coffee table as she had done with other (magazine, newspaper) articles I’d written.

It took me a while to realize that talking about fascinating autopsies I’d seen didn’t really go over well at dinner parties.

I’m a breast cancer survivor.

My late husband was very supportive of Enough Rope. Shortly before he died, he said his greatest wish for me was that I would be on an airplane and see someone reading it as I walked down the aisle. I’m beginning to believe that may happen someday.

I can twist my hands and elbows around 360 degrees. At the same time. Again, this is something it took me a while to learn not to do at dinner parties.

My father, who was a lawyer and loved Perry Mason, got me hooked on murder mysteries as a way to deal with the bouts of insomnia I had as a young teenager. He told me that if I got my mind into the “puzzle part” of such books, I would forget what I was stressing over and relax. It worked so well, I devoured everything Erle Stanley Gardner had ever written and then went on to Rex Stout, Agatha Christie, Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, John D. MacDonald, Robert B. Parker…the list is endless. This is also the reason why I believe that the plot of any mystery is what makes it, and that it must be character-driven. Thanks, Daddy.

I was a Marine Corps brat until I was fourteen. One of the bases we lived on was Camp Pendleton, in southern California. Years later, when I was doing my graduate internship at the Fulton County ME’s Office, I met a death investigator named Gene Horton who had been an MP at Pendleton and remembered my father. He was kind enough to let me pick his brains (no pun intended) about his life and job. I don’t know where he is now, but I hope that if he reads Enough Rope and Blood Will Tell, he’ll like Hollis Joplin.

Downtown Atlanta

Teddy, the inspiration for Joplin's cat Quincy

Doss at the launch party for Enough Rope in 2013

India, who is being written into book three